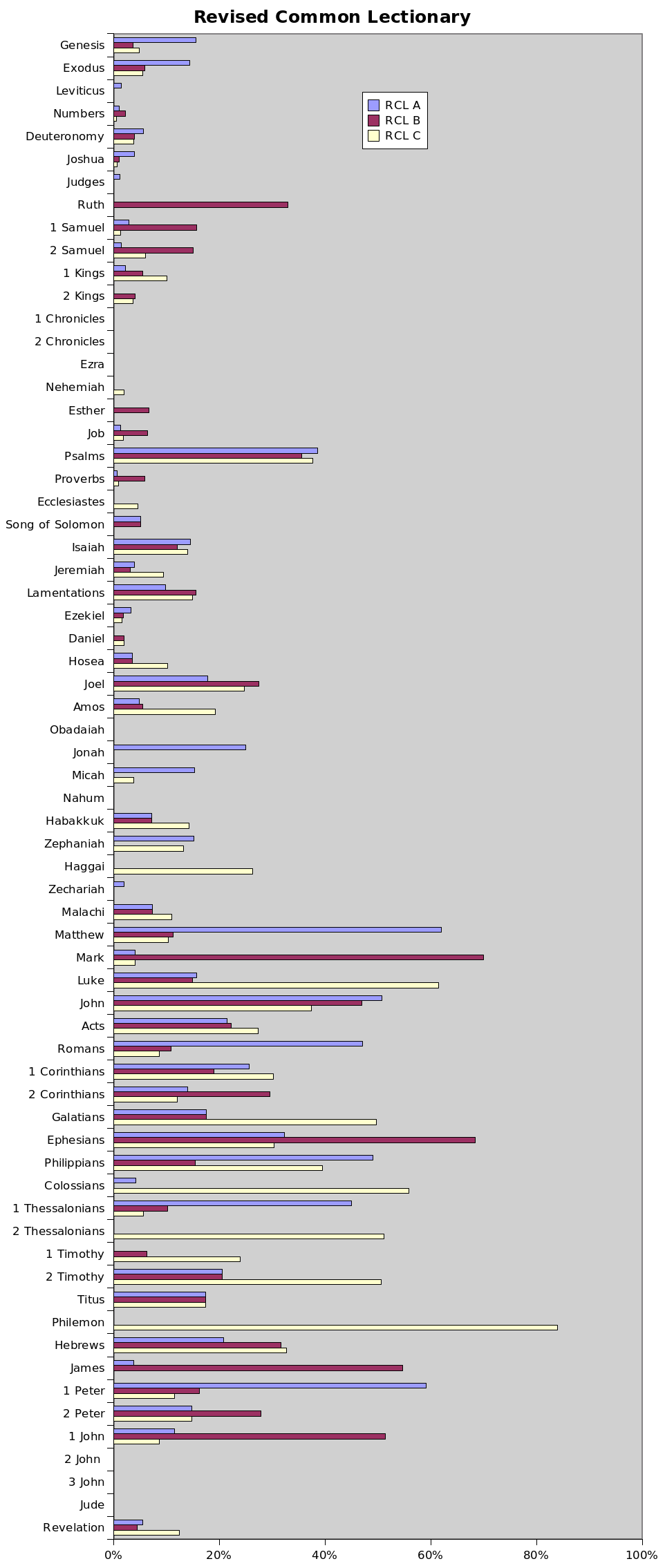

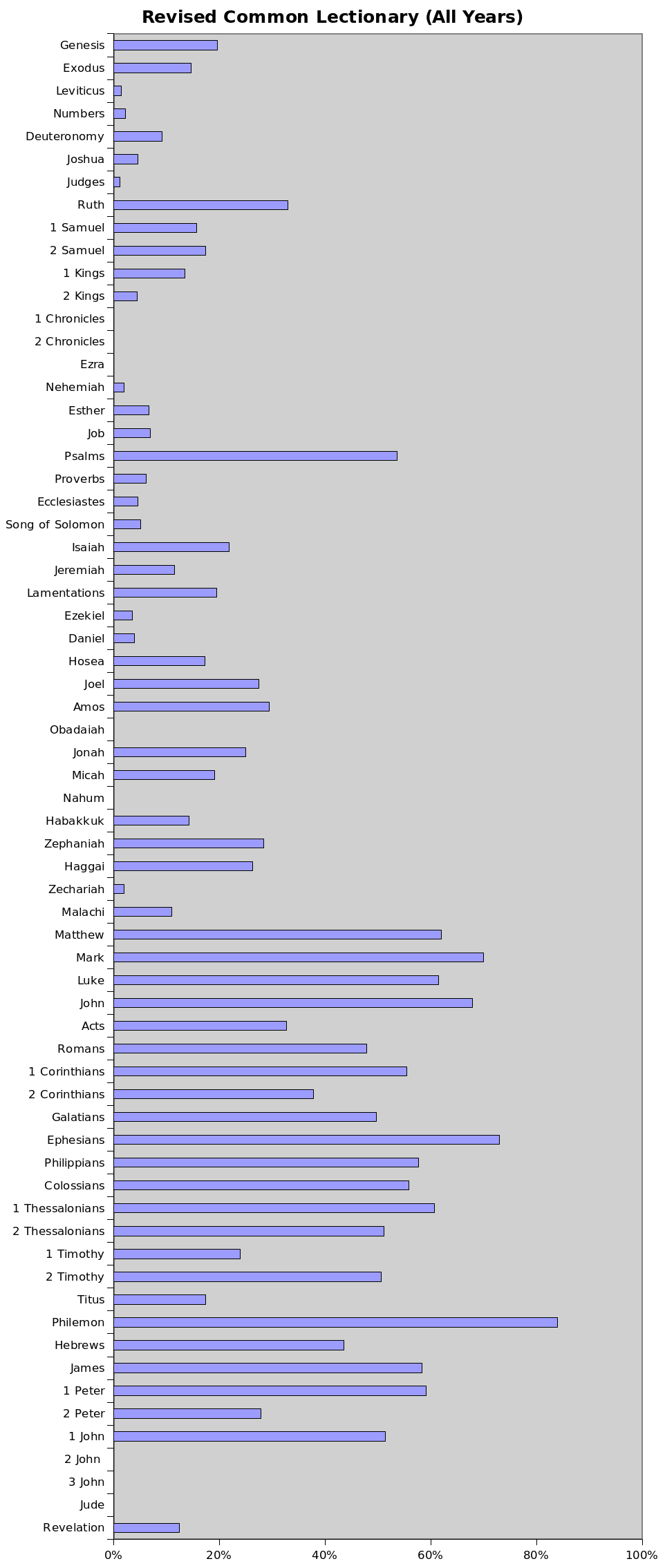

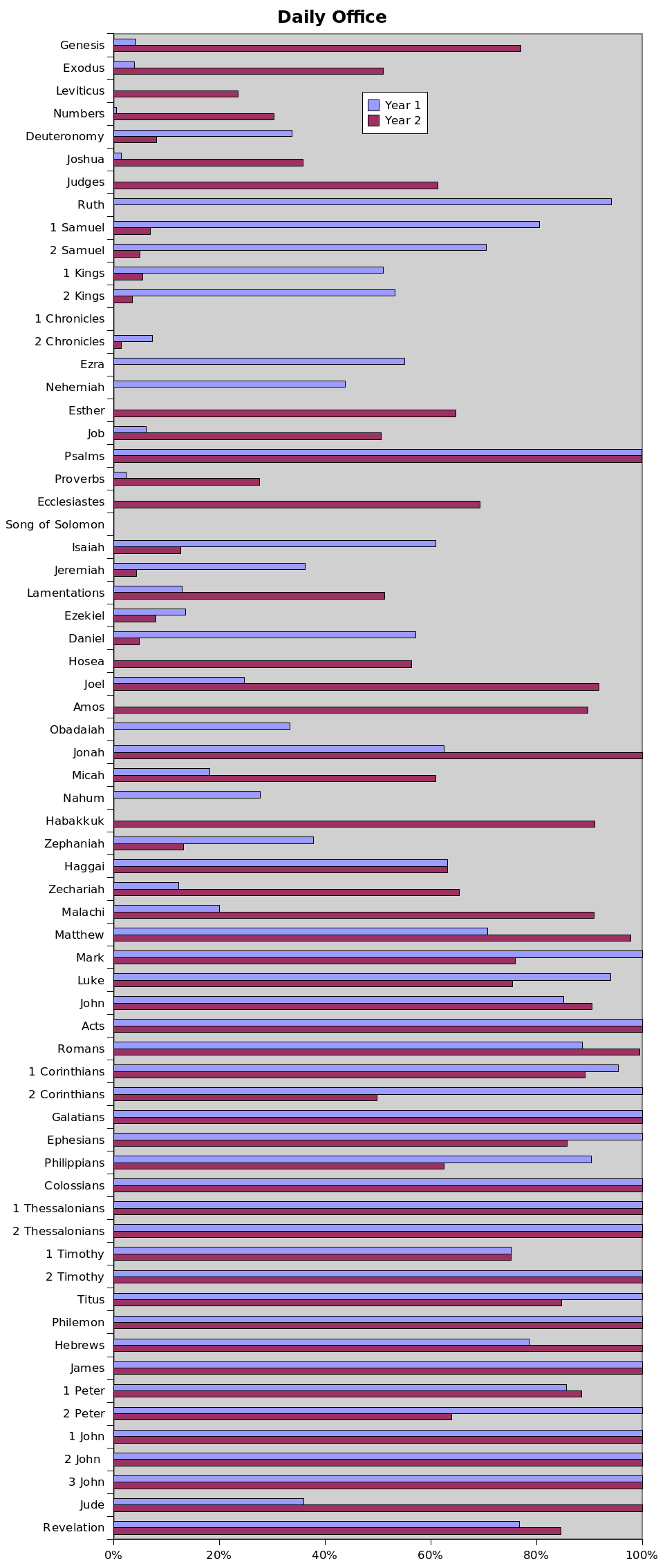

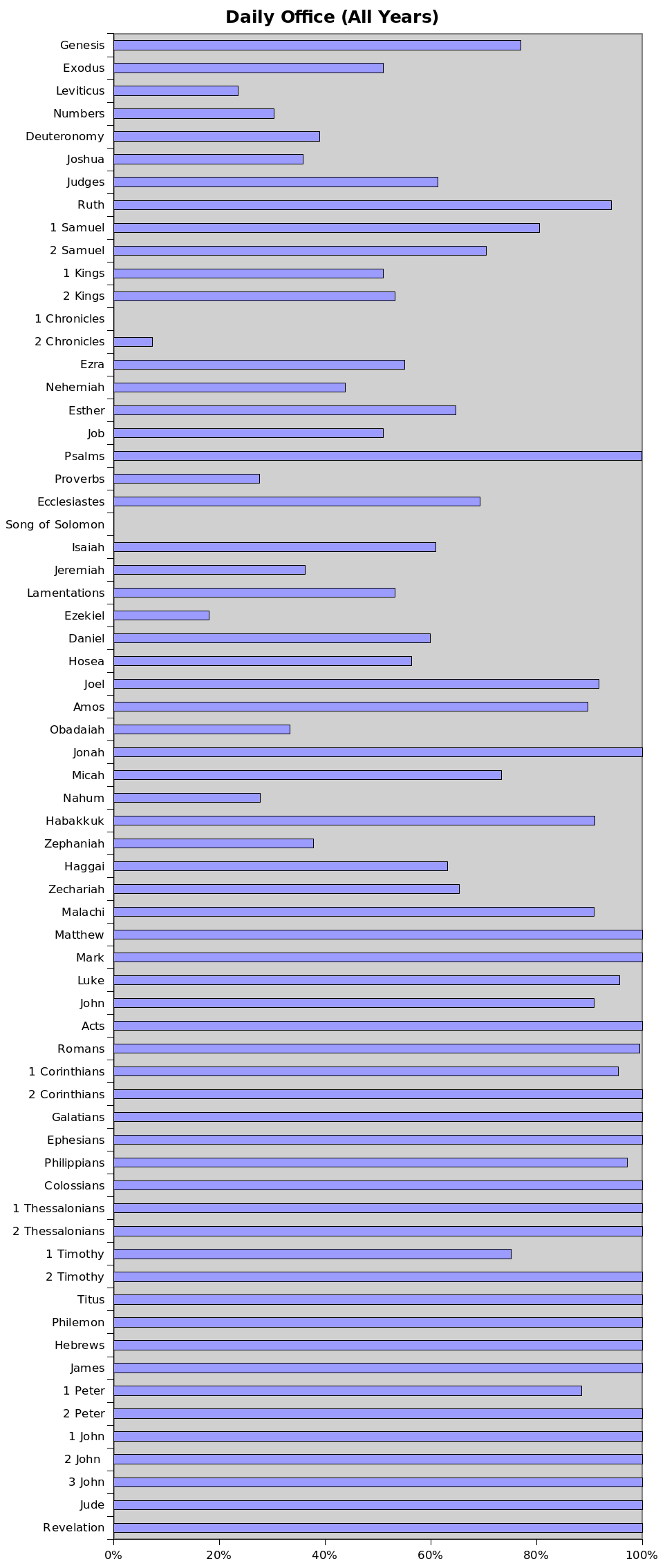

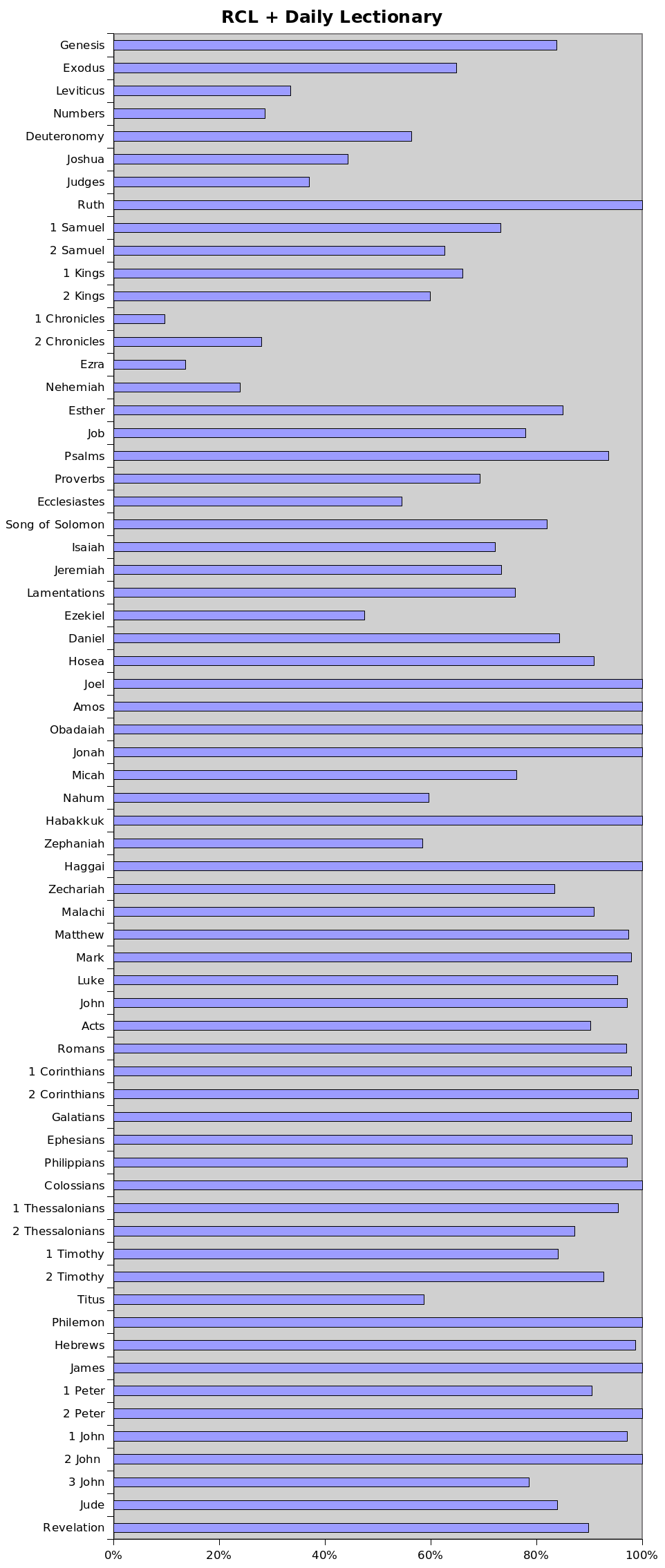

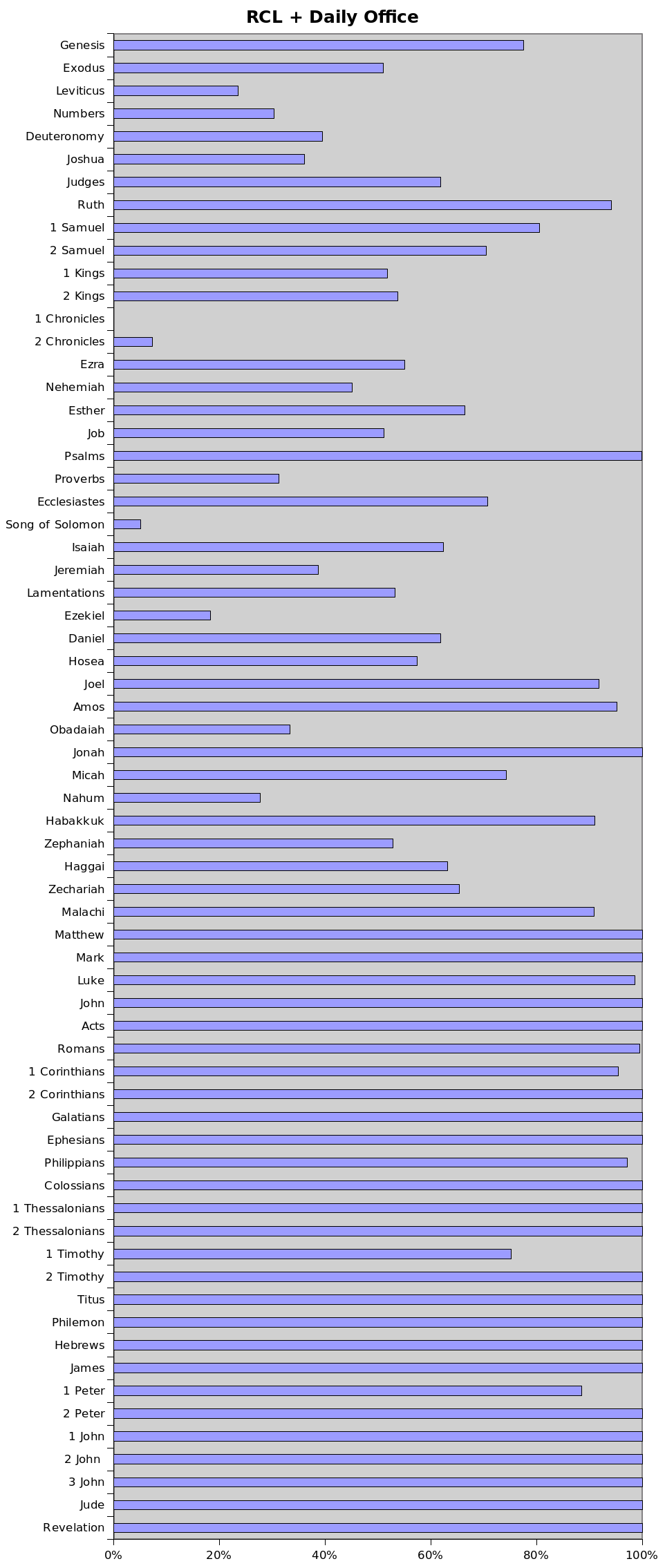

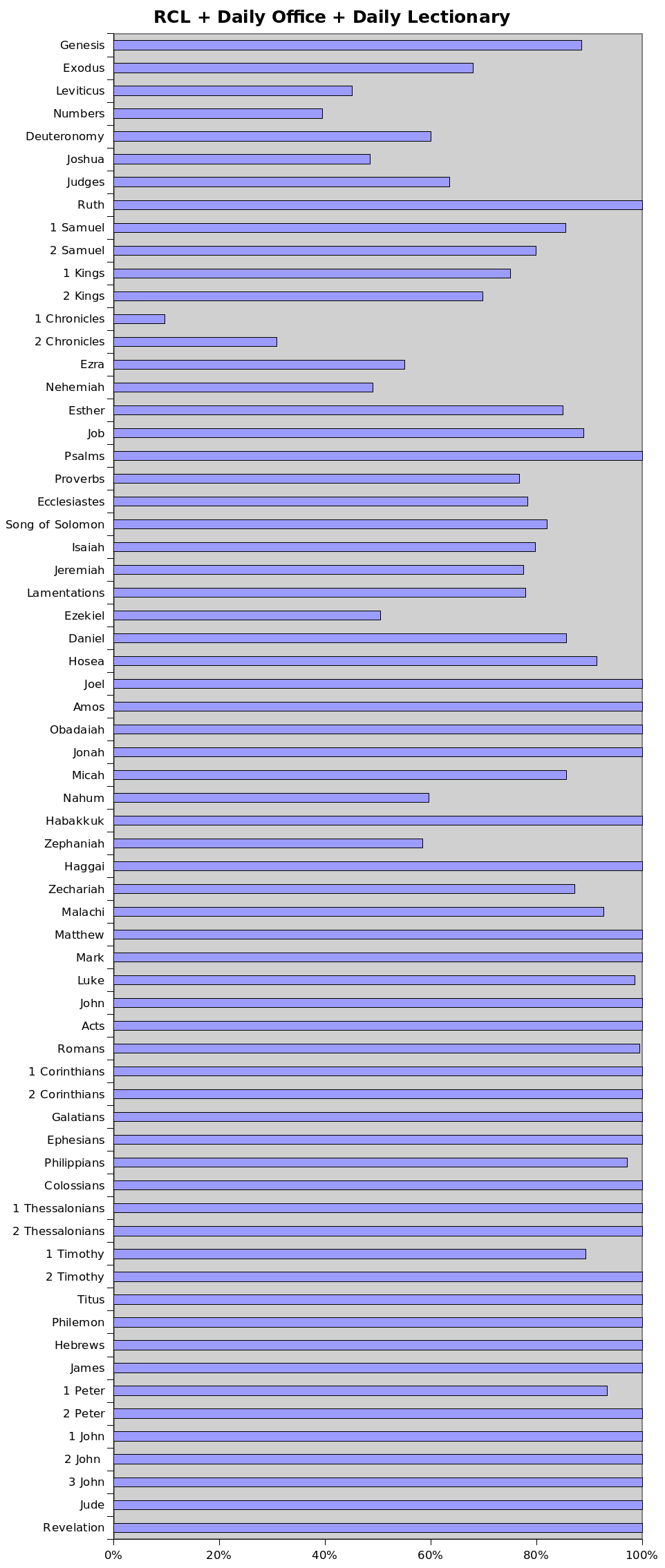

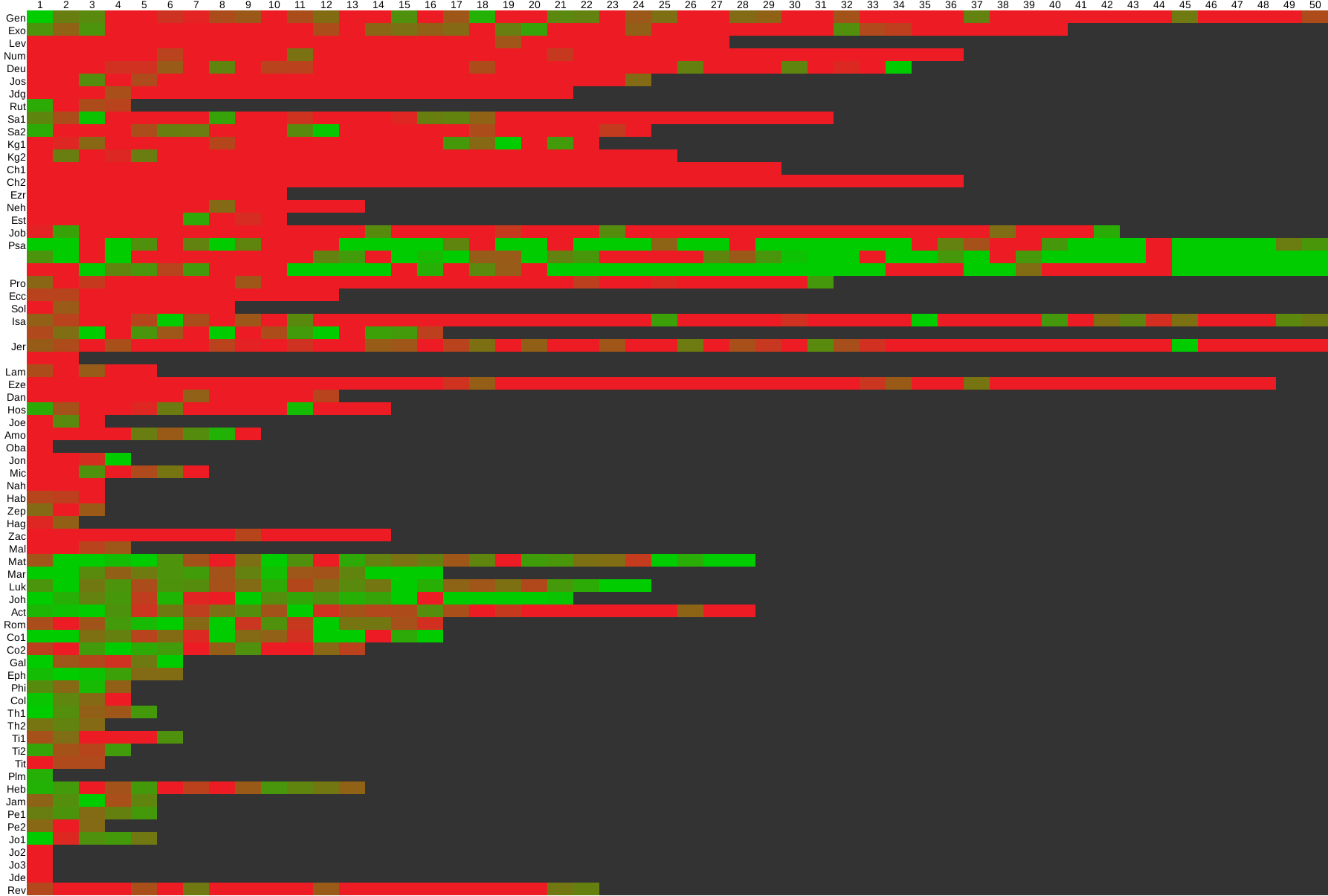

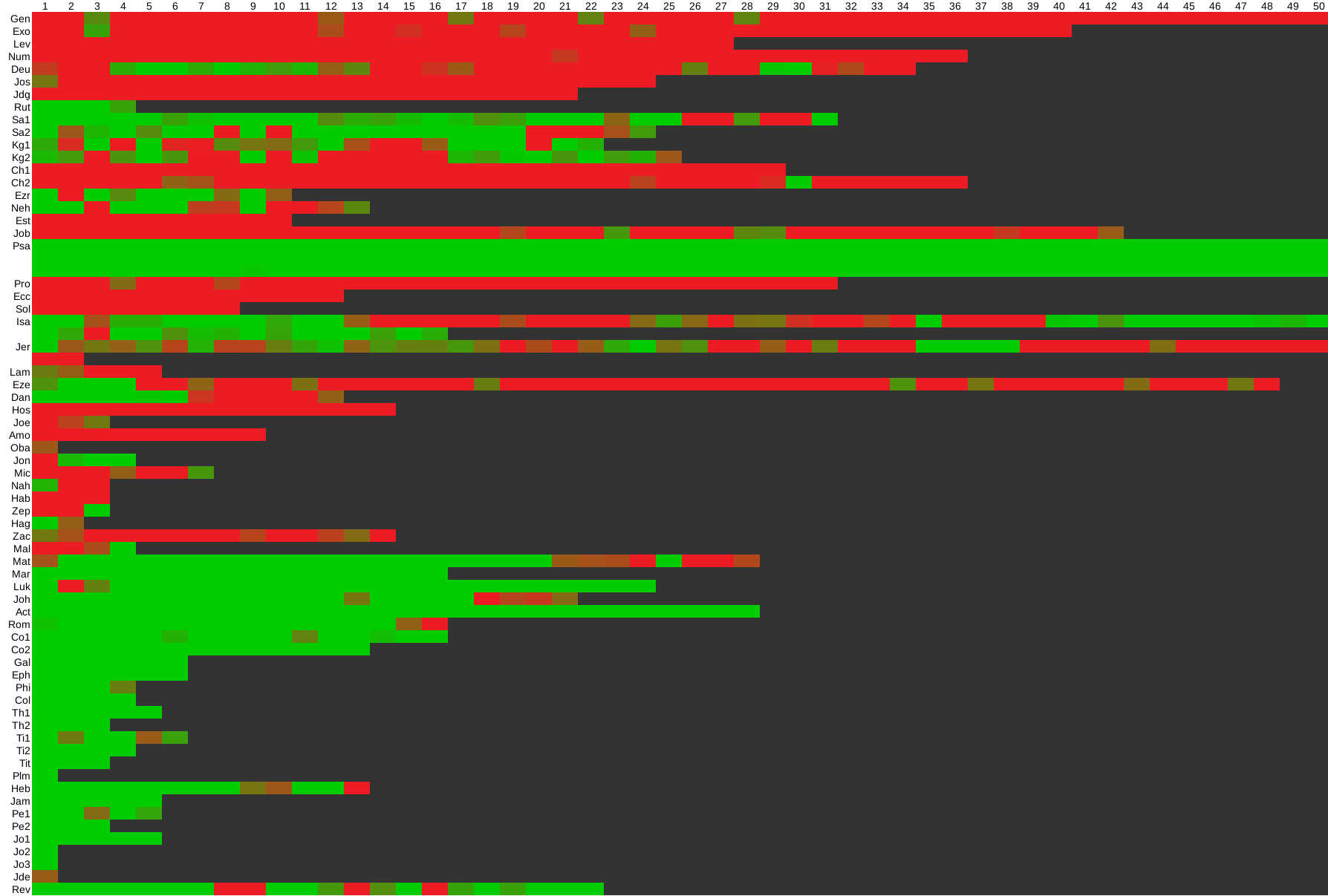

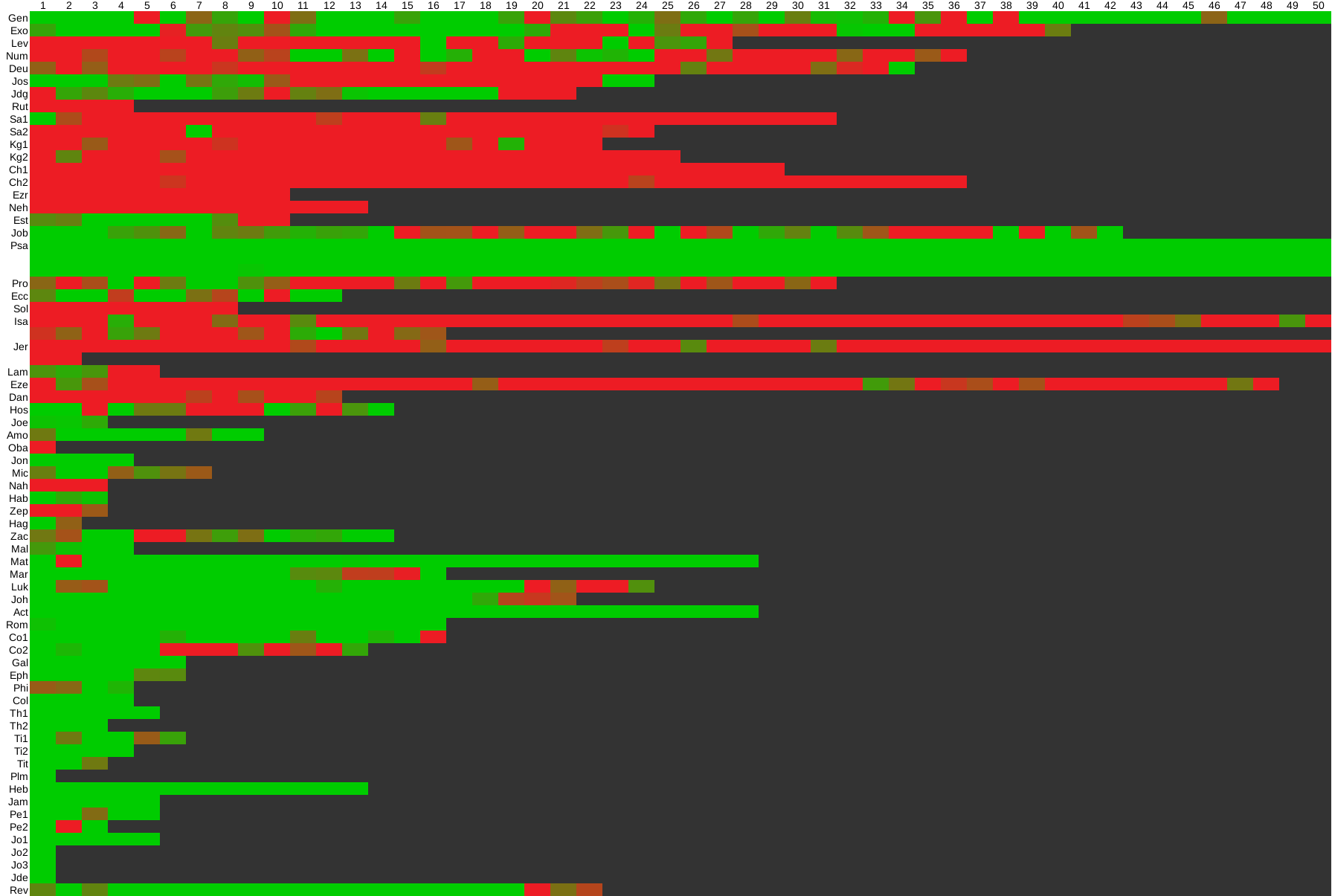

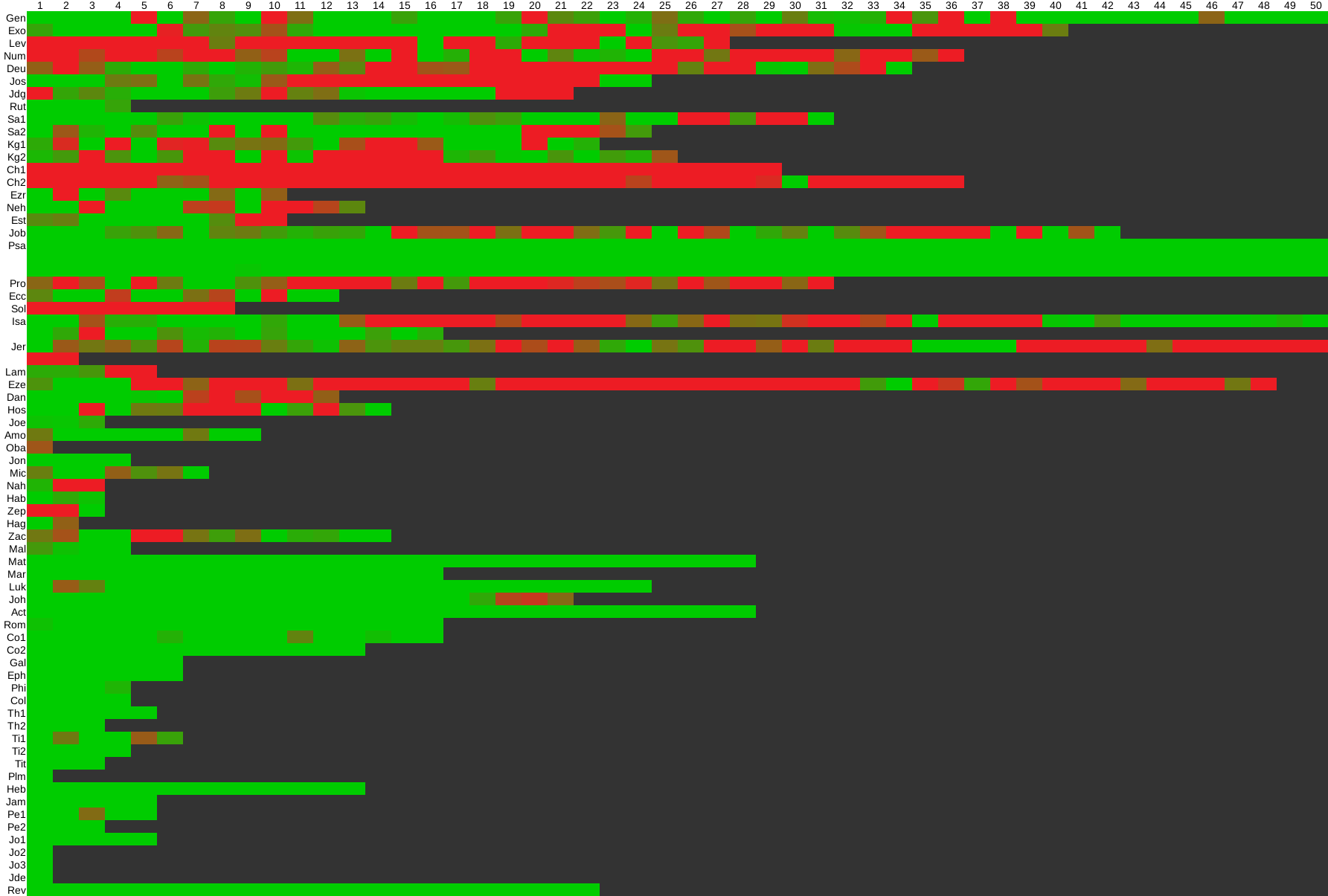

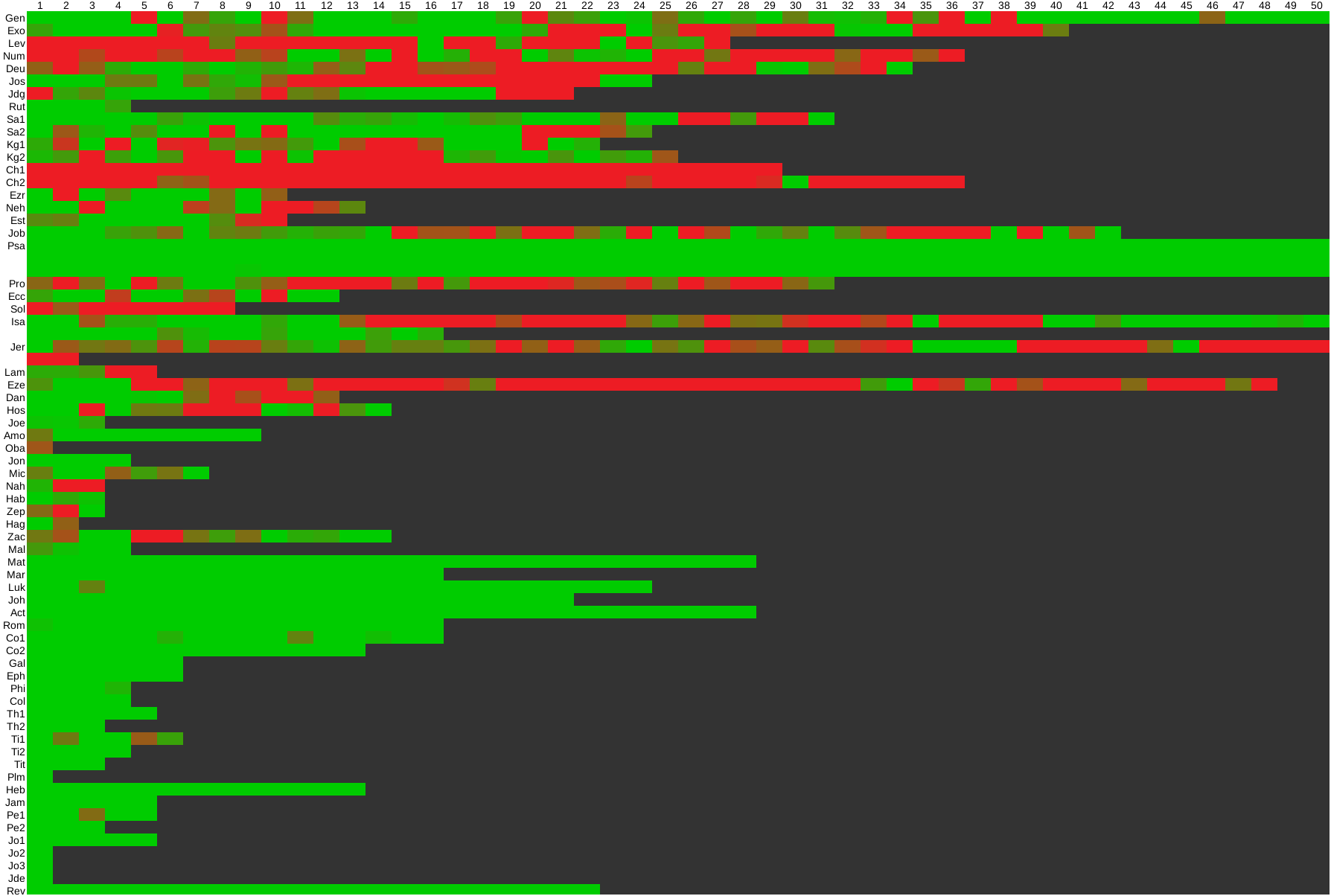

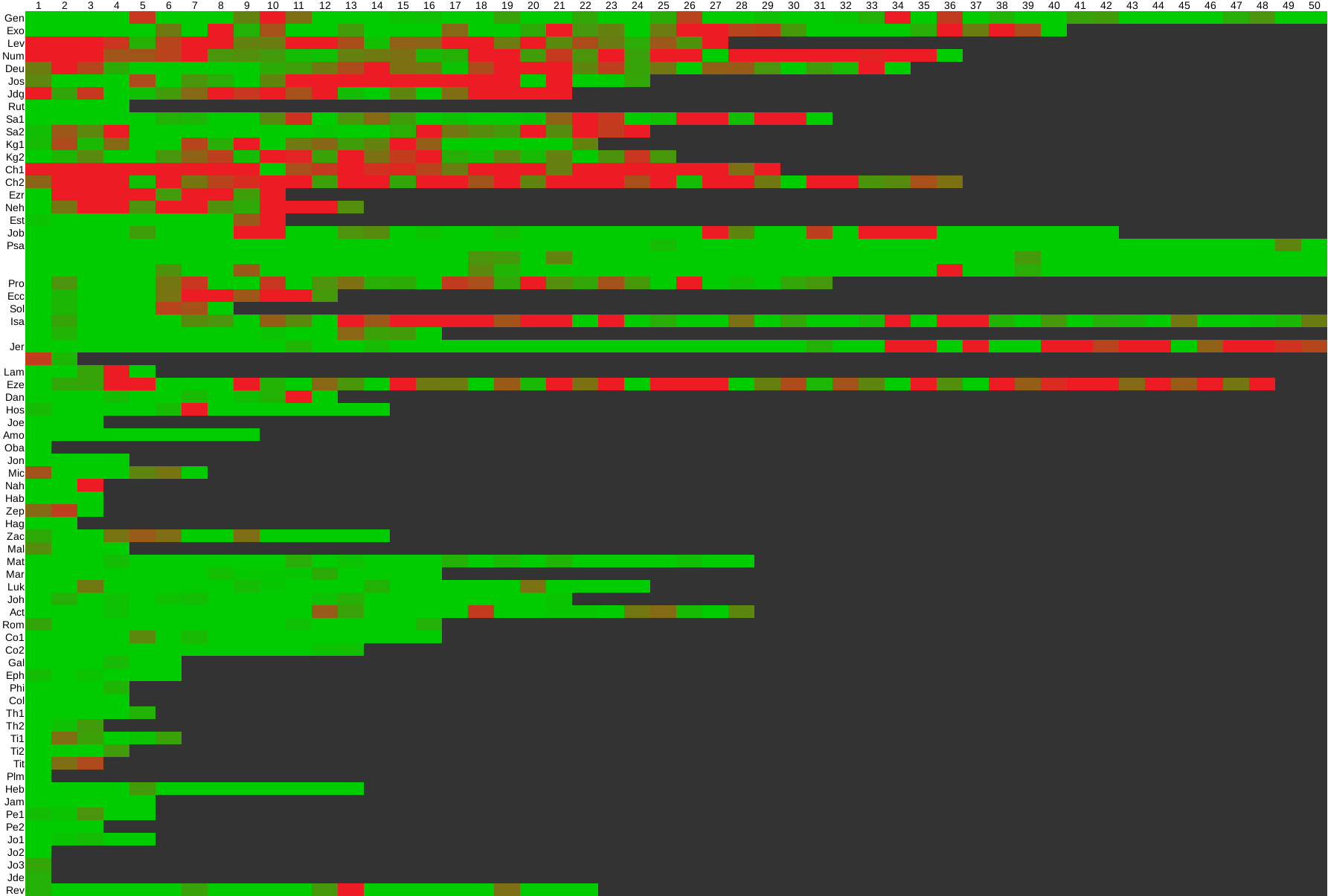

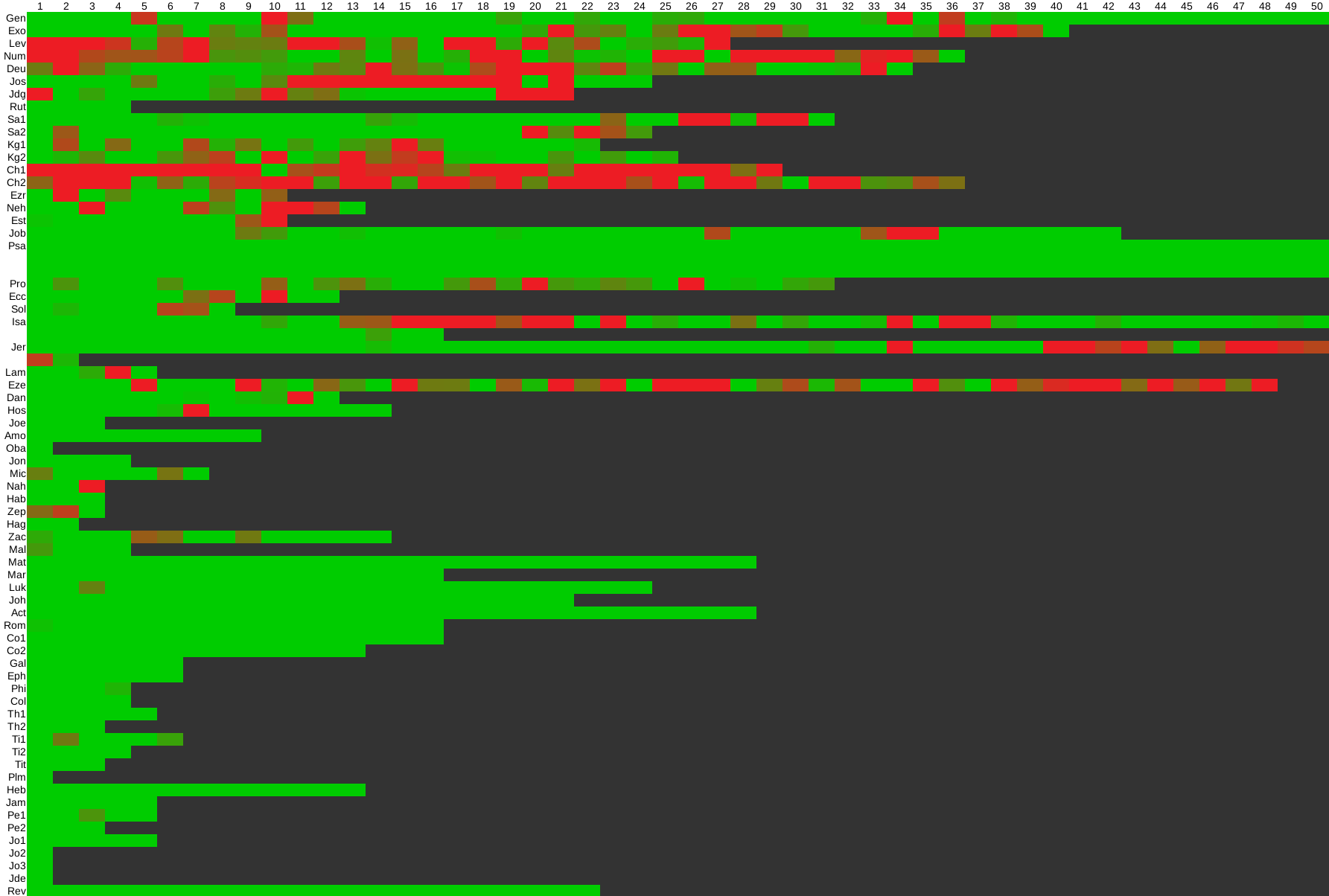

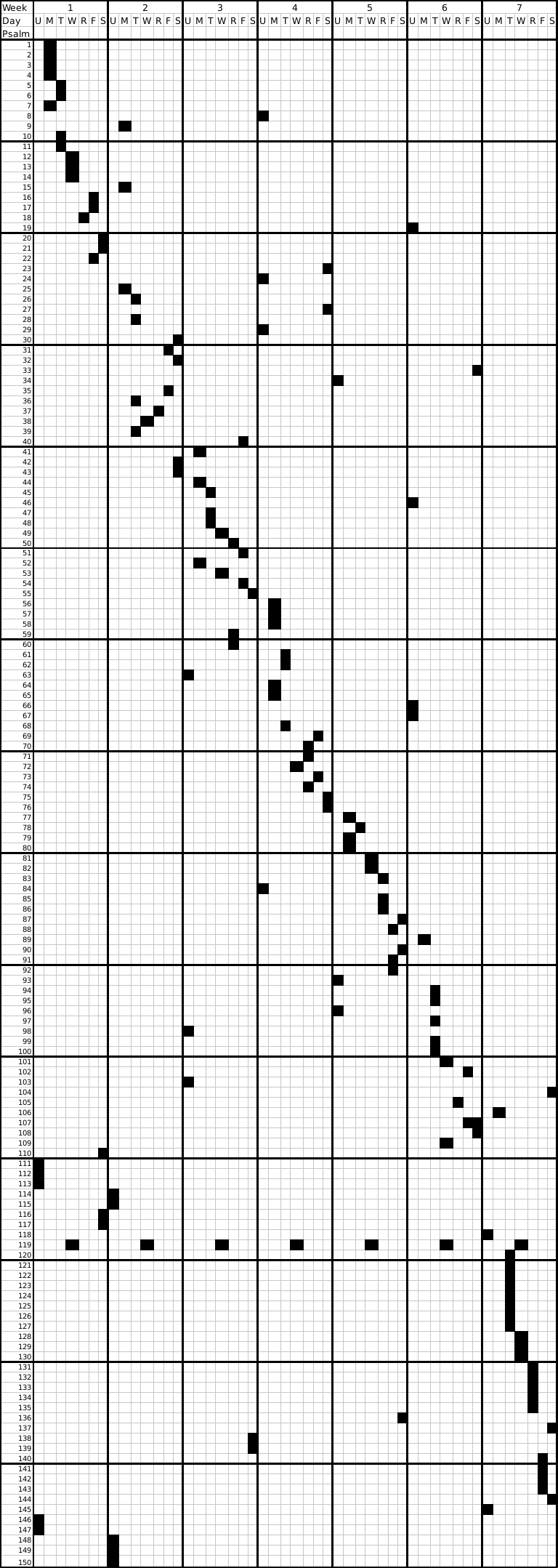

Lectionary StatisticsA lectionary is an organized sequence of readings from a holy text. Many Protestant churches use the Revised Common Lectionary to guide Bible readings during services. I've long been curious about how this lectionary is structured: what's included, what's excluded, and so on. This page presents various information of this type. [What is a lectionary?] [Which lectionary?] [What readings are covered?] [What's read the most?] [What's left out?] What is a lectionary?A lectionary appoints scripture readings for particular occasions. In the Christian tradition, these largely follow the church year, centered around Easter and Christmas. The year is divided into liturgical seasons: Advent is a four-week season of preparation prior to Christmas (which is celebrated for twelve days), Lent is a forty-day season of preparation prior to Easter, Epiphany is the season between Christmas and Lent, and so on. Lectionaries assign readings to Sunday services, following the theme of the season. Some lectionaries also appoint readings for weekdays, or for other special days in the church calendar, such as those commemorating an event or a particular person of faith. Lectionaries have a long tradition in Judaism and Christianity. Christian lectionaries date to the early church. They continue to this day in many denominations, and serve as an organizing tool to cycle through the major stories of the faith. Someone attending weekly services at a lectionary-based church will hear these texts at regular intervals. I grew up in the United Methodist Church and am now a member of the Episcopal Church, both of which use the Revised Common Lectionary. I was always curious about how the lectionary was structured, and especially curious about what was left out. This page reports some investigations I've done to this effect. Which lectionary do you use?A number of lectionaries exist. My particular faith communities use the Revised Common Lectionary, released in 1994 by the Consultation on Common Texts, and this is the lectionary I study here. The Revised Common Lectionary is used by a number of mainline Protestant denominations, and is based on the Ordo Lectionum Missae used by the Roman Catholic Church. Denominations may alter the Revised Common Lectionary to fit their particular traditions, and the specific version I will use is that found in the Episcopal Church's 1979 Book of Common Prayer, which can be viewed here. It involves a three-year cycle of readings, with each church year starting at the beginning of Advent (four Sundays before Christmas). Each Sunday is assigned four readings: one from the Old Testament, a psalm, one from the New Testament, and a reading from one of the Gospels. Two options are offered for the Old Testament readings: one option that is meant to correspond thematically with the Gospel reading, and another that is meant to provide continuity from week to week (e.g., telling the stories of a patriarch or king in sequence). The Book of Common Prayer also has a two-year cycle of readings meant for the Daily Offices of Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer. Each day is assigned one or more psalms (appointed either to morning or evening), and three readings (Old Testament, New Testament, and Gospel) that can be divided between the morning and evening offices. Naturally, a daily lectionary can cover more material than a Sunday lectionary. In general, the Daily Office lectionary does not align with the Sunday readings, aside from general thematic correspondence due to the season. In 2005, the Consultation on Common Texts produced a daily lectionary on a three-year cycle, intended specifically to align with the Sunday readings in the Revised Common Lectionary. The readings assigned to Thursday through Saturday anticipate the coming Sunday reading, those assigned to Monday through Wednesday provide reflection on what was read the previous Sunday. Each day is assigned there readings: a psalm, an Old Testament reading, and a New Testament reading. These readings can be viewed here. These lectionaries may be used in combination with each other. Here, I report analyses based on the Revised Common Lectionary alone; on the Daily Office alone; on the Revised Common Lectionary combined with the Daily Office readings; on the Revised Common Lectionary combined with the Daily Lectionary; and on all three lectionaries considered together. I don't report anything on the Daily Lectionary alone, because it is specifically intended to complement the Revised Common Lectionary. A few other odds and ends. On a few occasions, multiple options are given for the same day. For instance, there are three sets of readings given for Easter and Christmas, some intended for morning or evening services, and so on. Whenever multiple options exist, I assume that all of them will be read. I'm not aware of any church that would actually do this, but perhaps over time all of them might be used. This also means I include both Old Testament options for each Sunday in the Revised Common Lectionary. Some optional readings are taken from the deuterocanonical books (the so-called Apocrypha) found in the Catholic Bible, but not in most Protestant Bibles. In such cases an alternative reading is provided from the Protestant Bible. I have left out references to the Deuterocanon, not for theological reasons (indeed, the Episcopal Church deems them worthy of study, and I have enjoyed reading them myself), but for practical ones. Coverage of these books is very sparse compared to the Protestant canon, and the kinds of analysis I report here would not be as fruitful. I encourage any curious readers to extend my studies in this way! What readings are covered?Click on any image for the full-sized version. Coverage by bookThe charts below show the fraction of each book which is covered in the Revised Common Lectionary. The left chart distinguishes between the three years (A, B, and C). The right chart looks at the total fraction covered, including all three years. The left chart shows the three-year structure: for the most part, Year A tells the stories of the patriarches in the Old Testament, and Matthew's gospel in the New; Year B covers the history of the kings and Mark's gospel; and Year C has the writings of the prophets and Luke's gospel. (John's is distributed throughout the other years, and mainly used during special seasons.) The chart on the right gives a general impression of coverage. The New Testament is covered much more thoroughly than the Old. Some books are not read at all: 1 and 2 Chronicles, Ezra, Obadiah, Nahum, 2 and 3 John, and Jude are skipped entirely. Others are scarcely covered: Leviticus, Numbers, Judges, Nehemiah, and Zechariah are all given short shrift. Of course, time is limited during the main Sunday service! Let's see how the picture changes when we consider daily readings. The next two charts consider the Daily Office readings alone. The left chart distinguishes between the two years in the cycle, and the right chart combines them together. Both of the years cover almost the entirety of the New Testament. Year 1 focuses on the the period of the kings from the Old Testament, and Year 2 on the period of the patriarchs. The prophets are read in both years. Some books are still left out: 1 Chronicles and the Song of Solomon. 2 Chronicles is only lightly covered. The last three charts show the coverage of combinations of lectionaries: the Revised Common Lectionary together with the Daily Office; the Revised Common Lectionary together with the Daily Lectionary; and all three considered together. Now we're talking! Any combination of these provides much greater coverage, and should you decide to use all three lectionaries, you'll get at least something from each book. But there's still a bit missing! Keep on reading to find out what's left out, and why. Coverage by chapterThis section provides more insight into the coverage of each lectionary, by showing coverage of each chapter, not just coverage of each book. Each image below is a two-dimensional plot, with books on the vertical axis and chapters on the horizontal axis. Books with more than 50 chapters "wrap around" onto the next line. The cells are color-coded: bright red indicates no coverage (0% of that chapter), bright green indicates complete coverage (100% of that chapter), and the spectrum between them shows intermediate levels of coverage. Click on any image for the full-sized version. Revised Common Lectionary, Year ARevised Common Lectionary, Year BRevised Common Lectionary, Year CRevised Common Lectionary, CombinedDaily Office, Year 1Daily Office, Year 2Daily Office, CombinedRevised Common Lectionary + Daily OfficeRevised Common Lectionary + Daily LectionaryRevised Common Lectionary + Daily Office + Daily LectionaryDaily Office psalm cycleA bonus: outside of special seasons, the Daily Office is organized to cover all 150 psalms in a seven week cycle. This table shows when each psalm is read. I haven't distinguished between psalms appointed for Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, but I've found there is often a thoughtful choice about the particular service assigned. (For instance, references to the rising sun in psalms chosen for Morning Prayer, or to sleep in Evening Prayer.) Due to its length, Psalm 119 is divided among the seven Wednesdays in the cycle. The most famous psalms tend to be assigned to Sundays. What's read the most?This section lists the most frequently-occuring readings in the various lectionaries. Separate lists are provided for Old Testament, Psalm, and New Testament readings. Because a Psalm is appointed for each day, on average each psalm is read more frequently than other texts. Similarly, the New Testament is much shorter than the Old Testament. Providing separate lists makes it easier to identify relative frequencies. Revised Common Lectionary

Daily Office

Revised Common Lectionary + Daily Office

Revised Common Lectionary + Daily Lectionary

Revised Common Lectionary + Daily Office + Daily Lectionary

What's left out?This file is a listing of the 7043 verses not found in any of the lectionaries above: not in the Revised Common Lectionary, not in the Daily Office lectionary, and not in the Daily Lectionary. Good portions of the Old Testament are excluded; very little of the New Testament is. For the most part, these lacunae consist of reference material (genealogies, legal codes, temple specifications), stories told elsewhere (Chronicles vis-à-vis Samuel and Kings), particularly sordid or lurid material, and texts that can be easily taken out of context. This is not to say that such material is not worth reading or studying. In fact, I encourage people to go digging in corners that aren't often read. But much of this material simply wouldn't make for great reading Sunday morning. |